Let’s look at a common meeting issue that causes delay, swirl, frustration – and afterward, uncoordinated action. That classic phrase, “It depends.”

There has been good dialogue covering the topic at hand and the meeting facilitator is converging the group towards putting a stake in the ground. “So, we have discussed X, looked at Y, and understood more about Z. Is it fair to say that we should assume V will work?”

As people start to nod their heads, one of them submits, “Well, it depends.”

Pause. Halt. Drop Anchor.

You feel slightly irritated. It’s not that this person is a troublemaker, the devil’s advocator, the oxygen vacuum. It’s more likely they are a fair-minded, intelligent, and reasonable peer who collaborates well.

It’s just that you knew it might happen. The closer you get to requiring participants to commit verbally, the harder-to-discuss and tacit thoughts surface. The problem is that you only have this group for two, four, eight hours and you still have much ground to cover. You’ve just spent several minutes on this one item, was bringing it to a close, already thinking about where you’ll go next.

But someone just put their foot on the brake and triggered an emergency stop.

You ask him, “OK, can you say more?”, doing your best to keep the tone neutral. And he responds, “Well, I understand why you are asking if we can go forward assuming V will work, but it depends. You see, if A acquires B, V’s success is far from certain. But if A doesn’t acquire B, I think V is more viable. That’s why I’m not comfortable agreeing to move forward assuming V is OK, because we don’t know yet what A’s going to do.”

How do you respond? Do you break out of facilitating mode and become a domain expert, telling him that one of the two paths is most likely, “I don’t see A buying B in the next two years.” Nodding strongly as you say it so that he will nod back and accept that view.

Or does someone else resolve his dilemma, perhaps someone more senior; “John, it’s a good point. Yes, I see A buying B. Let’s assume that will be the case.” There is no dialogue. It’s a directive.

Either of these responses work in the moment to shut him up and get onto the agreement about V. But they don’t actually work because John just acquiesced to the group, thinking ‘There are bigger fish to fry.’ After the meeting, his actions, and inaction, are driven by the fact that he doesn’t agree with the assumption about V – because it still depends.

Or, he holds his ground and pushes the point. “No, I’m sorry, I’m not trying to slow us down but I think what A does will determine whether or not V is valid. And it’s just not certain yet what A will do.”

How do you get around this roadblock? How do you keep the meeting’s momentum and addess his valid point with a valid response in as little time as possible?

VUCA, first referenced in 1987, became a popular management term in recent years. Uncertainties are a specific category of planning assumption, where two or more outcomes may transpire. A might buy B, A might create a joint venture with B, A might not buy B, B might buy A, A might not buy B and create their own B-like operation. Each has a different impact on V and the path you should take to ensure the best outcomes for the topic at hand.

VUCA, first referenced in 1987, became a popular management term in recent years. Uncertainties are a specific category of planning assumption, where two or more outcomes may transpire. A might buy B, A might create a joint venture with B, A might not buy B, B might buy A, A might not buy B and create their own B-like operation. Each has a different impact on V and the path you should take to ensure the best outcomes for the topic at hand.

The formal discipline for handling uncertainties is Scenario Planning. However, this is typically a staged one or two day event deployed as pre-work into a business strategy revision. We needed to find a way to handle uncertainties real-time, on demand, as they arose within the discussion of any topic, to prevent groups getting stuck in meeting swirl.

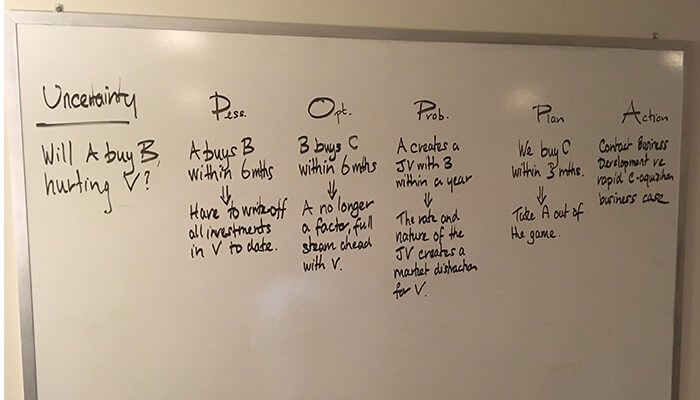

In future, as soon as you hear an uncertainty that is unresolved or invalidly resolved, deploy POPPA. Unresolved means that the uncertainty has been surfaced but the dialogue has not naturally converged on a point of view the group endorses. Invalidly resolved means a point of view has been forced on the group. Simply say to the group, “We have an uncertainty whose future outcome will influence what we should decide about V.” Go to the whiteboard, write the uncertainty and P, O, P, P, A across the top, like column headings.

At this point, you have a considered Planning assumption.

During the POPPA analysis, the person who expressed ‘It depends.’ has been checked with to ensure they concur with the logic in each step. Assuming so, you can conclude “We started with the uncertainty of what A would do related to B, and are moving forward on the assumption that A is most likely to….” You can now return to where you left off, “So, with this new Planning assumption, let’s agree on what will happen to V.”

Your first POPPA might take five to ten minutes. Groups gather speed as they become familiar with the protocol. Recently, during the course of helping develop a client’s digital strategy, a management consultant and her C-level clients surfaced 23 uncertainties and POPPA’d each of them into Planning assumptions.

Not only did this allow the strategy discussions to keep momentum, taking the uncertainties in its stride, everyone felt heard and supported the Planning agreements, with the succinct dialogue adding to their individual understanding of, and confidence in, their work.

Using POPPA in-the-moment during strategy development, decision-making, innovation ideation, business relationships, your plans are more valid for accommodating the uncertainty; then by monitoring how they transpire, you can adjust as required, suffering fewer negative surprises and catching more opportunities.

Are there uncertainties you face in your personal life, with colleagues, at a client? POPPA them, ideally with the parties involved.

To learn more about how to use POPPA plus other new collaboration methods, consider taking the Strategic Collaboration Methods education course.